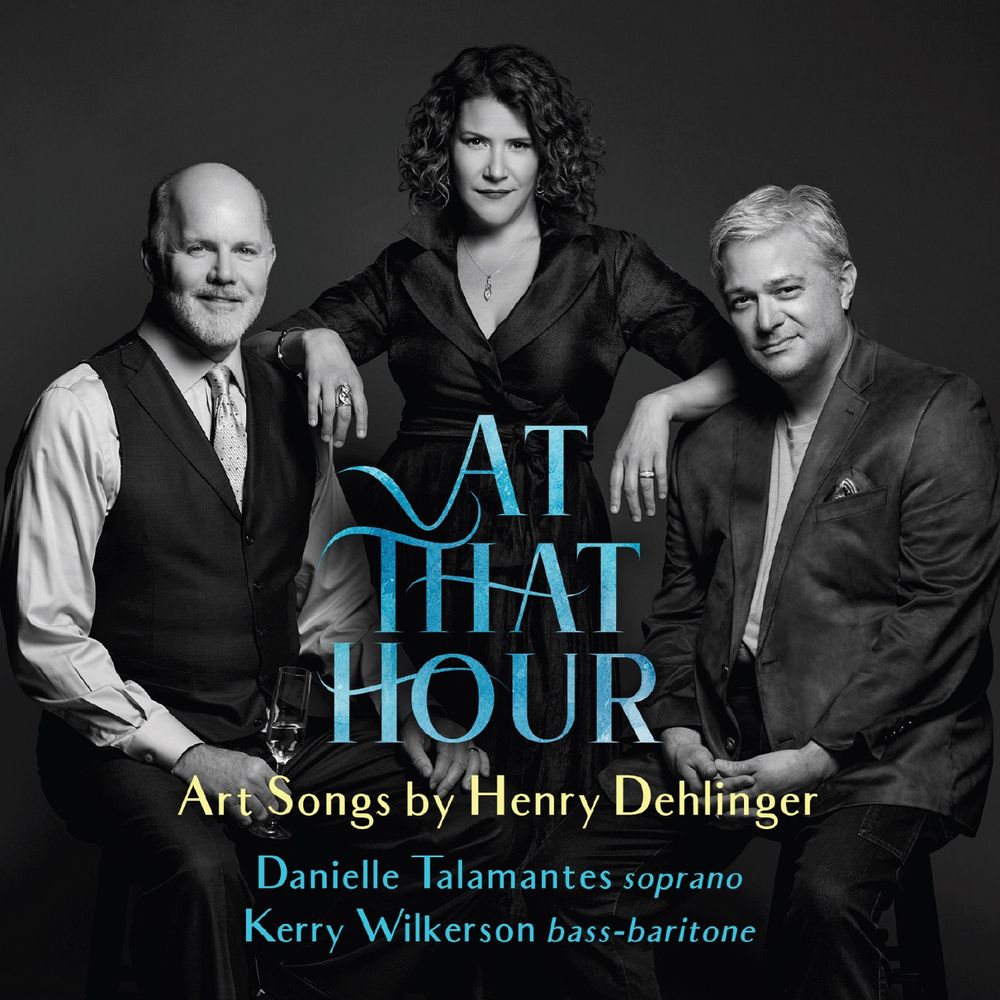

At That Hour

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

KERRY WILKERSON, bass-baritone

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

At That Hour

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

KERRY WILKERSON, bass-baritone

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

San Francisco-native Henry Dehlinger, a prodigiously talented pianist and singer, turned his hand to full-time composition in 2015. The skill and splendour of his music belies the relatively brief number of years he has committed pen to paper to create a considerable oeuvre of orchestral, chamber and choral music. His natural affinity for vocal music has also led to a number of works for solo voice. At That Hour is a superlative showcase for Henry’s craftmanship as well as his close collaborators, husband-and-wife team soprano Danielle Talamantes and bass-baritone Kerry Wilkerson. All of the songs on this original album of Henry’s art songs were written expressly for Danielle’s and Kerry’s impassioned voices.

The title track opens Henry’s 10-part song cycle set to texts by James Joyce. Inspiration for other songs comes from poetry by Dante, Edgar Allen Poe, Oscar Wilde, and Hebrew writings. Throughout, Henry’s modern yet tonal compositional voice shines through as he renders a diverse palette of musical styles to amplify the words he sets to music.

Program

At That Hour: Art Songs by Henry Dehlinger

Danielle Talamantes soprano

Kerry Wilkerson bass-baritone

Ten Poems of James Joyce

1. At That Hour When All Things Have Repose (3.47)

2. Bahnhofstrasse (4.22)

3. On the Beach at Fontana (3.36)

4. Simples (2.21)

5. Alone (3.18)

6. Flood (2.13)

7. Strings in the Earth and Air (3.25)

8. Night Piece (2.49)

9. Tutto è sciolto (2.04)

10. A Memory of the Player in the Mirror at Midnight (3.09)

11. Questa fiamma (T.S. Eliot) (3.01)

12. Amore e ‘l cor gentil sono una cosa (Dante) (3.51)

13. A Dream (Edgar Allen Poe) (2.10)

14. The Mount (Mark Riddles) (5.53)

15. Fragrance (Mark Riddles) (5.37)

16. Shir Hashirim (Biblical Hebrew) (8.15)

17. Requiescat (Oscar Wilde) (3.26)

Total time: 63.26

Program Notes

AT THAT HOUR

BY HENRY DEHLINGER

At That Hour is the world premiere recording of my compositions for solo voice. It marks the beginning of my association with AVIE Records and the culmination of a very productive period as a composer. The album was recorded in three days at Sono Luminus studios in rural Boyce, Virginia, but it was four years in the making. During this time, one of the great joys of my work has been the close and rewarding friendship I have forged with soprano Danielle Talamantes and bass-baritone Kerry Wilkerson.

This is the third album I have recorded with Danielle, and the first with Kerry. The first album Danielle and I recorded is Canciones españolas (2014), a collection of Spanish songs by Granados, Falla and Turina, which Gramophone lauded for its “musical excellence.” The second is Heaven and Earth: A Duke Ellington Songbook (2016), which features my arrangements of Ellington’s jazz standards. Audiophile Audition called it, “a knock-your-socks-off performance.”

Danielle and Kerry both light up the stage, as individual performers and as a husband-and-wife duo. That alone would make this new album special. What makes it unique is that the original works in this recital were composed especially for their voices.

At That Hour When All Things Have Repose is the inspiration for the album’s title and the first of my Ten Poems of James Joyce in this art song recital. A soft, rubato melody rises above the opening bass octave. The emphasis on the monosyllables establishes the text’s iambic rhythm. But the effect is a slowing of the tempo, thus achieving the “repose” intimated in the first line. “Play on, invisible harps, unto love” is emphasized by corresponding arpeggios in the piano, mimicking a harp. After a dramatic sweep to high C-flat, the soprano line, beautifully rendered by Danielle, descends back to a condition of repose.

In 1917, James Joyce suffered a sudden and painful attack of lumbago while walking along Bahnhofstrasse, the chic main street in Zurich, Switzerland. His condition was compounded by increasing blindness due to glaucoma. Bahnhofstrasse underscores Joyce’s angst as he discovers youth is fleeting. Yet, being middle-aged, he realizes he’s not old enough to benefit from the “old heart’s wisdom” that comes in the autumn of life. The musical language is minimalist and meditative, composed of repeating cycles of broken chords in the accompaniment that reiterate a simple, eerie motif as the melody floats wistfully above.

The existential theme continues in On the Beach at Fontana, which recalls an excursion that Joyce and his young son took on the Adriatic coast. It evokes the experience of paternal love, most especially the fear that would come with losing the boy. Agitato sixteenth notes in the accompaniment mimic the father’s fast-beating heart. Halfway through the piece, the soprano line strikes us with a series of dissonant tritones. Danielle adds a steely surety to these gorgeous dissonances as she renders the lines, “Around us fear, descending, Darkness of fear above.”

Just as On the Beach at Fontana evokes the poet’s love for his son, Simples captures his affection for his daughter as she gathers herbs in a garden in Trieste. It’s a lighthearted interlude before delving back to a more wistful theme. Alone conjures the image of a lazy, solitary evening. But a sensual thought enters, provoking “A swoon of shame.” Danielle masterfully sustains the word shame over six measures as it disappears into the nothingness of a faint hum. Flood dwells upon frustrated desire in a tone that is almost vain but always bombastic. Kerry appropriately evokes a hint of Eros in “Love’s full flood, Lambent and vast.”

Strings in the Earth and Air is a tender hymn of nature with impressionist overtones. The song’s sultry vocal line emerges from a progression of minor and dominant ninth chords in this jazz-inspired rendering of Joyce’s verse. Replete with ecclesiastical imagery, Night Piece is a reverent, if not haunting portrait of “night’s sin-dark nave.” With its soaring melody, the music swells into a tender exultation of the night sky. Joyce’s characteristic neologisms abound. A “star-knell” tolls as “upsoaring” clouds surge “voidward,” high above the “adoring waste of souls.”

Tutto è sciolto (“All is lost now”) is taken from an aria in the second act of La Sonnambula (“The Sleepwalker”), an opera by Vincenzo Bellini, one of Joyce’s favorite operatic composers. The aria is sung by Elvino who is distraught by the discovery of his fiancée, Amina, in Count Rodolfo’s bedroom, which she entered while sleepwalking. The title hints at the emotional turmoil of a failed seduction of a young girl Joyce once knew.

A Memory of the Players in a Mirror at Midnight completes the Joyce cycle. It underscores the anguish of aging and achieves its clarity of expression through its precise images. The “Players in the Mirror” likely refers to the English Players, a Zurich-based amateur theatrical company with which Joyce was involved during World War I.

Questa fiamma (“This Flame”) is the prelude of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, my rhapsody for voice and orchestra, adapted from the poem by T.S. Eliot and composed for Danielle. The text consists of six lines from Dante’s Inferno, which Eliot uses as an epigraph. The condemned soul of Guido da Montefeltro—now a tongue of flame in the eighth circle of hell— confesses all he knows, mistakenly assuming it would be impossible for Dante to betray his confession to the living. Sung in the original Italian, it is musically rendered as a sarabande, a slow, stately dance in triple meter.

When two of our dearest friends decided to marry, I wrote Amore e ‘l cor gentil sono una cosa (“Love and the gentle heart are one and the same”) as my wedding gift to them. The ceremony was in Florence, Italy on March 4, 2020, just before the world began to lock down in response to the coronavirus pandemic. What better text could I set than a love sonnet from La vita nuova by Dante, the revered Florentine poet? Danielle and Kerry’s heartfelt performance during the wedding reminded us that fear is not the most powerful emotion.

The first piece I wrote for Kerry is A Dream. It’s a setting of Edgar Allan Poe’s sonnet of the same name, and it expresses a profound yearning for a love long lost. It is, at once, emotive and melancholic.

The Mount and Fragrance are settings of poems by New York-based poet Mark Riddles in which he recasts familiar biblical passages in the sensory language of sight, in the case of The Mount, and smell, in Fragrance. The cycle was commissioned in 2015 by The Casement Fund, which supports new directions in creative writing, especially in connection with the other arts.

The Mount draws its inspiration from the mystical vision of the Transfiguration recounted in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. Phrygian dominant scales evoke the distinctively exotic sounds heard in Middle Eastern musical traditions and Jewish liturgical chants. Using the melodic themes established in The Mount, Fragrance presents olfactory images of rising incense and flower blossoms combined with Lazarus raised from the dead to symbolize the human journey from the profane to the sacred, mortality to incorruptibility.

Shir Hashirim (“Song of Songs”) is the third movement of Kohelet, my cantata in five movements for mixed chorus, soloists and orchestra. A setting of Song of Songs, this duet for soprano and bass-baritone combines lush, modal melodies and colorful harmonic textures with a reduction for piano. My wife Lauren, a Hebrew speaker and linguist by training, transliterated the gorgeous Biblical Hebrew text for me.

With Requiescat (“May She Rest”), I heard the blues a-calling me. The text by Oscar Wilde expresses his feelings of grief that accompanied his sister’s death two months before her tenth birthday. I rendered Wilde’s memoriam with a blues stride accompaniment, reminiscent of my arrangement of Duke Ellington’s Come Sunday. The subtitle—A “Wilde” Stride—is most apropos.

In the weeks leading up to recording, Kerry experimented with the closing line. It’s a jazzy, downward progression of four dominant ninth chords accompanying four syllables, Re-qui-es-cat. When the Eureka! moment struck, Kerry was all jazz hands. “You’ve got to think Kelsey Grammer,” he explained, “Tossed Salad and Scrambled Eggs!”

Bravo!

This recording has happened because of the support of many wonderful people. I would like to express my deepest thanks to my wife Lauren, for being my muse and for her love and enthusiastic encouragement. I could never have done it without her. Thanks also to Erica Brenner, dear friend and Grammy-winning producer whose refined aesthetic and creative judgment guided our project from recording to mastering; and Daniel Shores, Grammy-winning sound engineer from Sono Luminus, where our production thrived on a location recording setup where the acoustics were thoughtfully considered. Final thanks must go to our dear friend Sherry Watkins, stalwart supporter of the arts in the Washington, DC area, who hosted a musical soiree at her lovely home that funded the lion’s share of this project.

-Henry Dehlinger

Recorded 24 – 26 September 2019, Sono Luminus Studios, Boyce, Virginia, USA

Recording Producer and Editor: Erica Brenner

Recording, Mixing, Mastering: Daniel Shores

Piano Technician: Jon Veitch

Heaven and Earth - A Duke Ellington Songbook

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

Heaven and Earth - A Duke Ellington Songbook

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

2016 NEW RELEASE: In her sophomore album, Metropolitan Opera Soprano Danielle Talamantes crosses over into the realm of jazz with a recording filled with standard gems and rarely heard masterpieces. With arrangements by Henry Dehlinger, Larry Ham, Caren Levine, and Marvin Mills, this album’s charts were almost exclusively written for this very recording.

Listen to the album on SpotifyProgram

COME SUNDAY

Duke Ellington / Duke Ellington [arr. H. Dehlinger]

IMAGINE MY FRUSTRATION

Duke Ellington / Billy Strayhorn and Gerald Wilson [arr. H. Dehlinger]

IN A SENTIMENTAL MOOD

Duke Ellington / Manny Kurtz and Irving Mills [arr. L. Ham]

DO NOTHIN’ TILL YOU HEAR FROM ME

Duke Ellington / Bob Russell [arr. L. Ham]

PRELUDE TO A KISS

Duke Ellington / Irving Gordon and Irvings Mills [arr. L. Ham]

DON’T GET AROUND MUCH ANYMORE

Duke Ellington / Bob Russell [arr. H. Dehlinger]

SOPHISTICATED LADY

Duke Ellington / Irving Mills and Mitchell Parish [arr. H. Dehlinger]

I’M BEGINNING TO SEE THE LIGHT

Duke Ellington, Harry James and Johnny Hodges / Don George [arr. C. Levine]

SOLITUDE

Duke Ellington / Eddie Delange and Irving Mills [arr. C. Levine]

MEDITATION (piano solo)

Duke Ellington [arr. H. Dehlinger]

HEAVEN

Duke Ellington / Duke Ellington [arr. M. Mills]

ALMIGHTY GOD HAS THOSE ANGELS

Duke Ellington / Duke Ellington [arr. H. Dehlinger]

Program Notes

Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899-1974) is a colossus among American composers of any genre. With a career spanning more than 50 years, he wrote more than one thousand compositions, many of which have become jazz standards as well as precious, irreplaceable gems of the American Songbook. While music historians are won’t to view him as a jazz or big band swing composer, Ellington’s work reaches far beyond. Many musicologists have neglected the extensive body of sacred music that Ellington produced, four of which are presented in this album. In truth, Ellington did not consider himself a jazz or big band writer and performer. In his words, he wrote and played “the natural feelings of a people.”

Ellington conceived his works differently than others of the big band era. Typical arrangements of that period were written for a rhythm section supporting full sections of saxophones, trumpets and trombones with occasional short, improvised solos for contrast. Ellington was like a playwright, producing more script than manuscript, giving voice to leads within his cast of characters, then supporting the tale they wove with other voices within the cast. He chose his players not only for their musical proficiency, but also for their strong personalities. Unlike classic big band, Ellington encouraged his band to express themselves in their music, to let their individual personalities shine through.

The early works were often released as three-minute instrumental singles, the maximum time possible on the single side of a ten-inch 78 RPM record. Words were added later, sometimes several years later, and by a variety of lyricists, adding another sparkling—sometimes startling —dimension to the captivating saga. Whether an instrumental or vocal arrangement, these pieces carry away the listener with Ellington’s uniquely transcendent, supremely evocative, and unequalled style.

I first learned of Danielle and Henry’s Ellington project at a small gathering of musicians, a soiree of sorts, where artists, including some of Danielle’s most promising pupils from her voice studio, were performing works in progress and experimenting with concepts. When asked how she would follow her debut recording, Canciones españolas, Danielle thought aloud, “Possibly something out of the American Songbook…maybe an Ellington collection.” She and Henry had actually been performing two or three Ellington standards for some time, and they performed Larry Ham’s setting of In a Sentimental Mood for the gathering. Henry then improvised accompaniment for sections of a few other standards. It was obvious at that point that this idea was bound to become a beautiful new recording.

This collection captures the genius of Ellington’s compositions and the emotional range of the performers—soprano Danielle Talamantes and pianist Henry Dehlinger. It features settings written by Larry Ham, Caren Levine, Marvin Mills and—in his debut as an arranger—Henry Dehlinger. Danielle and Henry have collaborated extensively on both performance and recording (including Canciones), and Henry wrote his arrangements featured in this album specifically for Danielle’s voice (as did Levine and Mills with their arrangements of Solitude and Heaven, respectively).

The descriptions below include references to original, famous and historically significant versions of these compositions. While the performances in this collection certainly stand on their own, I encourage seeking out additional recordings to hear and compare how others have interpreted Ellington’s “stories.” While listening, ponder the circumstances, the times and places during which these treasures were created, and reflect on the effect on audiences across generations.

During Ellington’s lifetime, a chasm existed—or was, at least, perceived—between the disciplines of “serious music” (as orchestral or classical music was called) and jazz music. In a televised interview in 1966, Leonard Bernstein and Duke Ellington discussed an erosion of this divide. Both were seeing that the aficionados supporting symphony concerts were the same enthusiastic attendees at Ellington performances. Bernstein expressed to Ellington, “You were one of the first people who wrote so-called symphonic jazz. Maybe that’s the difference between us. You wrote symphonic jazz, and I wrote jazz symphonies.” This collection of American music is intelligently conceived, sensitively arranged, and beautifully performed. Duke Ellington once said, quite simply, “If it sounds good, it IS good.” Danielle, Henry and audiences alike can be confident: This collection, indeed, IS good.

-Scott Parrish, Raleigh, North Carolina

Soprano Danielle Talamantes is an international recitalist who made her Carnegie Hall debut in a solo recital in 2007. Since then, she has appeared as a soloist with the National Symphony Orchestra, Baltimore and Nashville Symphony Orchestras, National Philharmonic Chorale and Orchestra, United States Army Chorus, Choralis, Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Trujillo Symphony Orchestra and Seoul Philharmonic. Talamantes joined the Metropolitan Opera roster in the spring of 2011. In 2015, she made her Metropolitan Opera stage debut as Frasquita in Bizet’s Carmen. She made her Lincoln Center debut at Alice Tully Hall as the soprano soloist in the world premiere of Bob Chilcott’s Requiem and returned to the National Philharmonic in Beethoven’s Choral Symphony and Mozart’s Requiem and Exsultate, jubilate. Other highlights include the soprano lead in the world premiere production of Janice Hamer’s Lost Childhood with the National Philharmonic, Handel’s Messiah with the Phoenix Symphony, Mozart’s Mass in C minor with the City Choir of Washington and Donna Anna in Mozart’s Don Giovanni at Cedar Rapids Opera. She also sings the role of Violetta in La traviata at Cedar Rapids Opera and Finger Lakes Opera, Adina in L’elisir d’amore at Gulf Shore Opera and Mimí in La boheme at St. Petersburg Opera. Talamantes reprises her role as Frasquita and sings the role of Anna in Nabucco at the Metropolitan Opera in the 2016-17 season. Talamantes’ first place competition honors include the Irene Dalis Opera San Jose Competition, Irma M. Cooper Opera Columbus Competition, XII Concurso de Trujillo, NATS Artist Award and Vocal Arts Society Discovery Series competition. She earned her BA from Virginia Tech and MM from Westminster Choir College.

[ www.DanielleTalamantes.com ]

Pianist Henry Dehlinger has appeared on some of the world’s leading stages, including San Francisco’s War Memorial and Performing Arts Center and the White House in Washington, D.C. He has also appeared as featured soloist with The United States Army Chorus, guest performer on Washington’s Embassy Row, and in concert for notable public officials, including the President of the United States and the Prince of Wales. Celebrated for his interpretation of great Spanish piano works, in 2011, Dehlinger released his first album, Evocations of Spain, featuring selections from Isaac Albéniz’s Iberia and Enrique Granados’ Goyescas and 12 Danzas españolas. In 2013, Dehlinger began his artistic collaboration with soprano Danielle Talamantes which resulted in the critically acclaimed Canciones españolas album on MSR Classics. Heaven and Earth, Dehlinger’s second collaboration album with Talamantes, marks his debut as a jazz arranger. Born in San Francisco, Dehlinger started playing the piano at age six and singing at seven. His first mentor was the late conductor and choirmaster William Ballard of the San Francisco Boys Chorus, whom Dehlinger credits for his early success. By the time he was eleven, he had earned a reputation as a prodigious talent, performing with major orchestras under conductors such as Riccardo Chailly and Edo de Waart and at the San Francisco Opera with operatic legends Luciano Pavarotti, Montserrat Caballé and Giorgio Tozzi. At age twelve, Dehlinger became a pupil of renowned piano virtuoso Thomas LaRatta, founder and director of the Crestmont Conservatory of Music, with whom he continues his piano performance studies. Dehlinger graduated from Santa Clara University where he studied history and piano. [ www.HenryDehlinger.com ]

Canciones Españolas

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

Canciones Españolas

DANIELLE TALAMANTES, soprano

HENRY DEHLINGER, piano

2014 NEW RELEASE: In her debut album, Metropolitan Opera soprano Danielle Talamantes performs a gorgeous recital of Spanish songs from three of Spain’s greatest composers - Enrique Granados (1867-1916), Manuel de Falla (1876-1946), and Joaquin Turina (1882-1949).

Listen to the album on SpotifyProgram

ENRIQUE GRANADOS (1867 – 1916)

LA MAJA Y EL RUISENOR from GOYESCAS

CANCIONES AMATORIAS

Mira que soy niña

Mañanica era

Serranas de Cuenca

Gracia mía

Descúbrase el pensamiento

Lloraba la niña

No lloréis, ojuelos

MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 – 1946)

SIETE CANCIONES POPULARES ESPAÑOLAS

El paño moruno

Seguidilla murciana

Asturiana

Jota

Nana

Canción

Polo

JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882 – 1949)

TRES ARIAS, OP.26

Romance

El Pescador

Rima

Program Notes

In nearly every discussion about Spanish music we find that the composers represented in this recording – Enrique Granados (1867-1916), Manuel de Falla (1876-1946), and Joaquin Turina (1882-1949) – are placed among Spain’s standard bearers of musical nationalism. While we might be tempted to suspect this is simply a convenient construct of today’s musicologists, we will find that these composers indeed saw one another in the same light.

Consider Turina’s description of an encounter with Isaac Albéniz and Manuel de Falla in Paris, 1907: “. . . the three of us walked arm in arm along the Champs-Elysées. . . After crossing the Place de la Concorde, we sat in a tavern on Royal Street and there, with a glass of champagne and pastries, I experienced the most complete metamorphosis of my life. . . . There, Albéniz spoke of European music, and there I completely changed my views. We were three Spaniards on a corner in Paris and we owed it to Spain to make great efforts for our national music. I will never forget that scene nor will I forget that thin young man with us, the illustrious Manuel de Falla.”

The relationship between Falla and Turina had developed early in their careers, well before this encounter in Paris. They were both Andalucians – Falla from Cádiz and Turina from Seville – who had relocated to Madrid to benefit from the opportunities the nation’s capital afforded. At the beginning of the 20th century, by far the most lucrative path to follow was that of a zarzuelero, a composer of Spanish operetta. Unfortunately, neither composer experienced much success with their zarzuelas. In the case of Falla, he was further frustrated with the fact that although his opera, La vida breve, had, in 1904, won first prize in a competition sponsored by La Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, he could not find a company in Madrid to produce it. Meanwhile, an equally discouraged Turina curtailed attempts to write for the stage and enrolled at the national conservatory where he studied symphonic and chamber music, and piano under Falla’s teacher, José Tragó.

Stifled by the musical scene in Madrid and drawn, like so many composers, to the City of Light, Turina arrived in Paris in 1905. Falla followed in 1907. Paris was a mecca for foreign artists of all disciplines. During these years Spanish music was much in vogue in Paris and its composers flourished. Falla and Turina could now count within their circle Debussy, Ravel, Dukas, D’Indy, Viñes, and of course, Albéniz. Tragically, this vibrant artistic community was dispersed with the beginning of World War I in 1914.

Though forced to return to Madrid, Falla and Turina were not willing to abandon what they had learned from their French teachers. With teachers as eminent as Dukas and D’Indy, respectively, it must have been self-evident that there would be immeasurable value in retaining the knowledge that had been imparted to them. Thus, with patriotic fervor tempered by cosmopolitan ambition, they continued on their journey of “musica española con vistas a Europa.” Accordingly, as we listen to the works of these composers in the current recital program, we will hear much more than simple adaptations of Spanish folk music. Rather, each work exhibits a possibility along a rich spectrum of aesthetic synthesis.

The case is somewhat different with Enrique Granados, our third composer. The impact of Paris on his music was minimal in comparison to that of Falla and Turina. He was there only as a student, from 1887 to 1889, and returned to Spain long before the younger generation of Spaniards arrived. As a Catalan musician born in Lérida his work reflects three dimensions, each consistent with the geographic description of his adulthood home, Barcelona. It is a city located in Catalonia, a region fiercely independent of Castile and Andalucía. The city is a major population center that nevertheless, has strong cultural ties to the rest of Spain. Also, it is also regarded as a major European city at a crossroads of international commerce and culture. Yet, we will find that Granados was not a strict regionalist. He published songs in both Castilian and Catalan. Without doubting the importance of his beloved Barcelona, we will see that he looked to Madrid as the true capital of the nation.

Granados was not present at the famous 1907 meeting in Paris. However, as a contemporary and friend of Albéniz, Granados was regarded by both Falla and Turina as an elder statesman from whom they drew inspiration in a manner similar to Albeniz. Thus, the bond between these composers is complete – a bond created not retroactively by historians, but by the composers themselves. It is a bond of admiration, friendship, national pride, and inspiration.

These composers pledged to write Spanish music. We need to ask ourselves, what did they mean by this? Does Spanish music derive from Andalucía, Castile, Catalonia? And when was it formed, in Spain’s royal courts and cathedrals in the 16th – 17th centuries, during the “golden” era when the nation was a military, economic and cultural superpower, or was it formed in the gypsy caves of Granada or the arid plains of La Mancha? And how much of what we hear as Spanish music owes a debt to foreigners? Was French Impressionism “an invasion of vulgarity from the north” as some early-20th-century Spanish critics contended, or was it a missing ingredient that, once discovered by Spaniards such as Turina and Falla, helped catapult Spanish music to the world stage? Each of our composers answered these questions differently, yet each did so authentically. Their different approaches will be evident as we look more closely at the repertoire presented on this recording.

La maja y el ruiseñor (The Maiden and the Nightingale, 1915), by Enrique Granados, speaks of two worlds. An aria from his opera, Goyescas, it is spectacular in its Romantic exuberance, harmonic lushness and sweeping lines. Yet, the opera itself speaks of Madrid in early times, during the era of the lower-class yet flamboyant majos and majas of the late 18th century so aptly depicted in the paintings of Francisco Goya.

Granados reaches further into the past with Canciones amatorias (1913). In his authoritative biography on Granados, Walter Clark observes that all of the texts of Canciones amatorias are Castilian romances that date from before 1700. They represent the Siglo de Oro, the golden century of which we have spoken. Clark further notes, “Granados’s celebration of Castilian poetry from a bygone era of imperial glory is consistent with his fixation on Castile and Madrid as the spiritual and cultural fulcra of the nation.”

When we survey the total output of our three composers, it is abundantly evident that Falla was the most progressive, even radical. He wholeheartedly embraced Debussy’s Impressionism, with its dense yet consonant harmonies, in works such as Noches en los jardines de España, while at other times he incorporated the biting polytonality of Stravinsky with Retablo de Maese Pedro and the Harpsichord Concerto. Yet, Falla was also deeply committed to the folk music of Spain. So much so that in 1922 he and García Lorca traveled the Andalusian countryside seeking out true practitioners of cante jondo, the “deep song,” that is an essential component of what we understand as flamenco music today.

It is no surprise then, that despite his radical leanings, Falla would set Siete canciones populares españolas (Seven Popular Spanish Songs, 1914), in a manner not far removed from their folk origins. Having selected these songs from previously published cancioneros, or song collections, Falla presents a pan-Iberian, rather than a regionally myopic, vision of his native land. El paño moruno and Seguidilla murciana are from southeastern Spain while Asturiana refers to Asturias, in the northwest of the country. Falla again crisscrosses the country with the Jota, originating in the northeastern region of Aragon, and Nana and Polo representing Andalusia in the far south. In Falla’s arrangements, the characteristic elements of Spanish folk music – dance rhythms, asymmetrical phrases, modal harmonies, and references to the guitar – lie near the surface, thereby retaining their energy and regional identity.

Written in 1923, Turina’s Tres arias draws upon three Romantic poets of the 19th century, Duque de Rivas (1791-1865), Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer (1836 – 1870), and José de Espronceda (1808 – 1842). The first, Romance, is a revival of a literary form, the romance fronterizo. These “frontier ballads” often idealized Moorish Spain, mixing historical events with love stories. Given Turina’s devout Catholicism, it might be surprising to realize that he chose a poem in which the protagonist is a Moor who has just defeated the Christian forces at Toledo. However, his interest in such themes was consistent with the times in which he lived. At the end of the 19th century and continuing into the early 20th, it was common in some Spanish intellectual circles to celebrate – even exaggerate – the Arabic contributions to Spanish culture and to romanticize the exotic, oriental culture of the Arabs which flourished in medieval Spain. There were, of course, many who opposed such views and sought to narrate Spain’s cultural history quite differently. This debate was especially lively among music historians of the time.

Turina’s early biographer, Federico Sopeña, speaks of Turina’s setting of Bécquer’s Rima with eloquence: “The Rima placed in the collection Tres Arias seems to be among the most masterful of this genre. At a stroke and with a vigorous tone, Turina successfully united the Romantic with the Andalusian without having to present the latter element in a literal manner. The melody arises in perfect linear fashion, intense and delicate – a Bécquerian paradox – and, with an enchanting simplicity, faithfully following the poetry, it exclaims or whispers of that mysterious beyond in which this poetry always leaves us.”

As we explore Spain through the vocal compositions of three of the country’s greatest composers, that “mysterious beyond” draws near.

-William Craig Krause

Goyescas / Goyaesque

La maja y el ruiseñor / The Maiden and the Nightingale

Fernando Periquet Zuaznábar (1873 – 1940)

¿Por qué entre sombras el ruiseñor entona su armonioso cantar? ¿Acaso al rey del día guarda rencor y de él quiera algún agravio vengar?

¿Guarda quizás su pecho oculto tal dolor, que en la sombra espera alivio hallar, triste entonando cantos de amor?

¿Y tal vez alguna flor,

temblorosa del pudor de amar,

es la esclava enamorada de su cantar?

¡Misterio es el cantar

que entona envuelto en sombra el ruiseñor! ¡Ah! Son los amores como flor,

como flor a merced de la mar.

¡Amor! ¡Amor!

¡Ah! No hay cantar sin amor.

¡Ah! Ruiseñor, es tu cantar himno de amor.

Why, in darkness, does the nightingale

sing his harmonious song?

Does he bear a grudge against the king of day and wish to avenge some insult?

Perhaps he hides in his breast such a grief he hopes to relieve in the darkness, sorrowfully singing love songs?

And perhaps some flower,

trembling from the embarrassment of love, is the spellbound slave of his singing?

Mysterious is the song

the nightingale sings in darkness! Oh, love is like a flower,

a flower at the mercy of the sea.

Love! Love!

Oh, there is no singing without love.

Oh, nightingale, your song is a hymn to love.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

1

Canciones amatorias / Love Songs

Mira que soy niña / Look, I’m Just a Little Girl

Anonymous

Mira que soy niña,

¡Amor, déjame!

¡Ay, ay, ay, que me moriré!

Paso, amor, no seas a mi gusto extraño, no quieras mi daño,

pues mi bien deseas;

basta que me veas sin llegárteme.

¡Ay, ay, ay, que me moriré!

No seas agora, por ser atrevido, desagradecido Con la que te adora;

Que así se desdora

Mi amor y tu fe.

¡Ay, ay, ay, que me moriré! Mira que soy niña…

Look, I’m just a little girl, Love, leave me be!

Alas, for I will die!

Gently, love, don’t thwart my pleasure,

don’t wish me harm,

since it’s my wellbeing you desire;

it’s enough that you see me without coming near. Alas, for I will die!

Now don’t be ungrateful, just for the sake of it, with the one who adores you;

for that will tarnish

my love and your faith.

Alas, for I will die!

Look, I’m just a little girl…

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

2

Mañanica era / It Was Daybreak

Anonymous

Mañanica era, mañana

de San Juan se decía al fin, cuando aquella diosa Venus dentro de un fresco jardín tomando estaba la fresca

a la sombra de un jazmín:

Cabellos en su cabeza, parecía un serafín.

Sus mejillas y sus labios como color de rubí,

y el objeto de su cara figuraba un querubín.

Allí de flores floridas hacía un rico cojín,

de rosas una guirnalda para el que venía a morir lealmente por amores sin a nadie descubrir.

It was daybreak, the morning of Saint John at last arrived, when the goddess Venus was in a cool garden

taking in the fresh air

in the shade of a jasmine tree:

The hair on her head

was like a seraph’s.

Her cheeks and lips

were the color of rubies,

and the expression on her face looked like a cherub’s.

Then with flower blossoms,

she fashioned a luxurious pillow, and a garland of roses

for the man who came to die faithfully for love

revealing his secret to no one.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

3

Serranas de Cuenca / Mountain Girls of Cuenca

Luis de Góngora (1561 – 1627)

Serranas de Cuenca iban al pinar,

unas por piñones, otras por bailar.

Bailando y partiendo las serranas bellas un piñón por otro de Amor las saetas huelgan de trocar, unas por piñones, otras por bailar.

Serranas de Cuenca iban al pinar,

unas por piñones, otras por bailar.

Entre rama y rama, cuando el ciego dios pide al Sol los ojos por verlas mejor, los ojos del Sol

las veréis pisar: unas por piñones, otras por bailar.

The mountain girls of Cuenca went to the pinewood,

some for pine nuts,

others to dance.

The beautiful mountain girls danced while cracking

one pine nut after another, Cupid’s arrows

they merrily averted, some for pine nuts, others to dance.

The mountain girls of Cuenca went to the pinewood,

some for pine nuts,

others to dance.

Between the branches, when the blind god beseeches the sun for eyes to better see the girls,

on the sun’s eyes,

you will see the girls tread; some for pine nuts,

others to dance.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

4

Gracia mía / My Graceful One

Anonymous

Gracia mía, juro a Dios

que sois tan bella criatura, que a perderse la hermosura, se tiene de hallar en vos.

Fuera bienaventurada

en perderse en vos mi vida, porque viniera perdida para salir más ganada.

Seréis hermosuras dos

en una sola figura;

que a perderse la hermosura se tiene de hallar en vos.

En vuestros verdes ojuelos nos mostráis vuestro valor, que son causa del amor,

y las pestañas son cielos: nacieron por bien de nos; de ellos nace mi locura.

Gracia mía, juro a Dios

que sois tan bella criatura, que a perderse la hermosura, se tiene de hallar en vos.

My graceful one, I swear to God you are so beautiful a creature, that if beauty were lost,

it would be found in you.

It would be a blessing

for me to lose my life in you, for it would be lost

only to come out richer.

You will be two beauties in one sole figure;

that if beauty were lost, it would be found in you.

Your bright green eyes

display their preciousness,

for they inspire love,

your eyelashes are heavenly, created for our delight;

from them is born my madness.

My graceful one, I swear to God you are so beautiful a creature, that if beauty were lost,

it would be found in you.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

5

Descúbrase el pensamiento / Unveil the Thought

Anonymous

Descúbrase el pensamiento de mi secreto cuidado, pues descubren mis dolores mi vivir apasionado.

No es de agora mi passion, días ha que soy penado: una señora a quien sirvo mi servir tiene olvidado.

Su beldad me hizo suyo,

el su gesto tan pulido

en mi alma está esmaltado.

¡Ay de mí, que la mire para vivir lastimado,

para llorar y plañir

glorias del tiempo pasado!

Unveil the thought

of my well-kept secret, and unveil my anguish, my life of suering.

My anguish is not new,

I have suered for days: a lady I serve

has forgotten my service.

Her beauty made me hers, her refined manner

is emblazoned in my soul.

Woe is me, that I gazed on her only to live in sorrow,

to weep and mourn

the glories of times gone by!

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

6

Lloraba la niña / The Girl Wept

Luis de Góngora (1561 – 1627)

Lloraba la niña,

y tenía razón,

la prolija ausencia de su ingrato amor.

Dejóla tan niña, que apenas creyó que tenía los años que ha que la dejó.

Llorando la ausencia del galán traidor,

la halla la luna

y la deja el sol.

Añadiendo siempre pasión a pasión, memoria a memoria, dolor a dolor.

¡Llorad, corazón, que tenéis razón!

The girl wept,

and with reason,

the prolonged absence of her ungrateful lover.

He left her so young

that she could hardly believe it was so long ago

he left her.

Weeping over the absence of her faithless lover,

the moon finds her

and the sun abandons her.

Always more

suering on suering, memories on memories, anguish on anguish.

Weep, dear heart,

for you have every reason!

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

7

No lloréis, ojuelos / Don’t Cry, Bright Eyes

Lope de Vega (1562 – 1635)

No lloréis, ojuelos, porque no es razón que llore de celos quien mata de amor.

Quien puede matar no intente morir,

si hace con reír más que con llorar.

No lloréis, ojuelos…

Don’t cry, bright eyes, for there is no reason to cry out of jealousy if you kill out of love.

One who can kill

does not try to die,

if you do more with laughing than with crying.

Don’t cry, bright eyes…

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

8

Siete canciones populares españolas / Seven Spanish Folksongs

El paño moruno / The Moorish Cloth

Gregorio Martínez Sierra (1881 – 1947)

Al paño fino, en la tienda, Una mancha le cayó.

Por menos precio se vende, Porque perdió su valor.

¡Ay!

Seguidilla murciana / Seguidilla Dance of Murcia

Traditional Folksong

Cualquiera que el tejado Tenga de vidrio,

No debe tirar piedras

Al del vecino.

Arrieros semos;

¡Puede que en el camino, Nos encontremos!

Por tu mucha inconstancia, Yo te comparo.

Con peseta que corre

De mano en mano;

Que al fin se borra, Y creyéndola falsa, ¡Nadie la toma!

On the delicate cloth, in the shop, There dropped a stain.

It sells for less,

As it has lost its value.

Alas!

If your roof is

Made of glass tile,

You’d better not throw rocks On your neighbor’s roof,

We are mule drivers;

Maybe along the way,

We’ll meet each other!

For all your fickleness,

I compare you

To money that passes

From hand to hand;

Which in the end is wiped out, And, believing it to be fake, No one takes it!

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

9

Asturiana / Asturian Song

Traditional Folksong

Por ver si me consolaba, Arrimeme a un pino verde, Por ver si me consolaba.

Por verme llorar, lloraba. Y el pino como era verde, Por verme llorar, lloraba.

Jota / Jota Dance

Traditional Folksong

Dicen que no nos queremos Porque no nos ven hablar; A tu corazón y al mío

Se lo pueden preguntar.

Ya me despido de tí,

De tu casa y tu ventana,

Y aunque no quiera tu madre, Adiós, niña, hasta mañana.

To see if it would console me, I drew near a green pine tree, To see if it would console me.

Seeing me weep, it wept;

And the pine tree, being green, Seeing me weep, it wept.

They say we we’re not in love Because they don’t see us talk; To your heart and mine

They can ask.

Now I take my leave of you,

Of your house and your window,

And although your mother doesn’t wish it, Goodbye, dear child, until tomorrow.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

10

Nana / Lullaby

Traditional Folksong

Duérmete, niño, duerme, Duerme, mi alma, Duérmete, lucerito

De la mañana.

Nanita, nana, Nanita, nana, Duérmete, lucerito De la mañana.

Canción / Song

Traditional Folksong

Por traidores, tus ojos,

Voy á enterrarlos;

No sabes lo que cuesta, “Del aire,” niña, el mirarlos. “Madre, á la orilla”

“Madre”

Dicen que no me quieres, Y a me has querido… Váyase lo ganado,

“Del aire,” por lo perdido. “Madre, á la orilla” “Madre”

Go to sleep, child, sleep, Sleep, my soul,

Go to sleep, bright little star Of the morning.

Lulla-lullaby,

Lulla-lullaby,

Go to sleep, bright little star Of the morning.

Your treacherous eyes,

I shall bury;

You don’t know how much it hurts,

“For heaven’s sake,” to look at them, girl. “Oh, mother, I’m on the edge!”

“Oh, Mother!”

They say you don’t love me,

Yet once you loved me…

Forget what is gained,

“For heaven’s sake,” for what is lost. “Oh, mother, I’m on the edge!”

“Oh, mother!”

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

11

Polo / Polo Dance

Traditional Folksong

“¡Ay!”

Guardo una pena en mi pecho, !Que á nadie se la diré!

¡Malhaya el amor, malhaya,

Y quien me lo dió á entender! “¡Ay!”

“Alas!”

I bear a sorrow in my breast, Of which I will tell no one!

Love be damned, damned,

And him who made me understand it! “Alas!”

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

12

Tres Arias / Three Arias

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

13

Romance / A Romance

Ángel de Saavedra, Duque de Rivas (1791 – 1865)

En una yegua tordilla,

Que atrás deja el pensamiento, Entra en Córdoba gallardo Atarfe el noble guerrero,

El que las moriscas lunas Llevó glorioso a Toledo Y torna con mil cautivos Y cargado de trofeos.

Las azoteas y calles Hierven de curioso pueblo, Que en él fijando los ojos, Viva, viva, está diciendo.

Las moras en los terrados Tremolan cándidos lienzos, Y agua de azahar dan al aire Y sus elogios al viento.

Y entre la festiva pompa, Siendo envidia de los viejos, De las mujeres encanto,

De los jóvenes ejemplo.

A las rejas de Daraja, Daraja la de ojos negros Que cuando miran abrasan, Y abrasan con sólo verlos,

Humilde llega y rendido

El que triunfante y soberbio, Fué espanto de los cristianos, Fué gloria de sarracenos.

Mas ¡ay! que las ve cerradas Bien distintas de otro tiempo, En que damascos y alfombras

On a dapple-grey mare,

Resplendent beyond comprehension, There enters into Cordoba

Atarfe, the dashing and noble warrior.

He led the Moors

To glory in Toledo

And returns with a thousand captives And triumphal trophies.

The rooftops and streets Bristle with curious spectators, Who fix their eyes upon him, And cheer, “Viva!”

The Moorish women on the terraces Wave their white handkerchiefs, Throw orange blossom water in the air And sing their praises to him.

And, amid the festive pageantry, He is the envy of his elders, Delight of the women,

And hero of the youth.

He nears the balcony of Daraja, Daraja, whose dark smoldering eyes Would burn as she gazed at him, And burn at his mere glance.

Humble and devoted, he arrives, He who, triumphant and proud, Was the menace of the Christians, And the glory of the Saracens.

But, alas, he sees her doors shut Much unlike a time gone by, When fine silks and rugs

14

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

Las ornaron en su obsequio. Adorned the entryway in his honor.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

15

El Pescador / The Fisherman

José de Espronceda (1808 – 1842)

Pescadorcita mía, Desciende a la ribera,

Y escucha placentera

Mi cántico de amor; Sentado en su barquilla, Te canta su cuidado, Cual nunca enamorado, Tu tierno pescador.

La noche el cielo encubre Y calla manso el viento, Y el mar sin movimiento También en calma está; A mi batel desciende,

Mi dulce amada hermosa, La noche tenebrosa

Tu faz alegrará.

De conchas y corales Y nácar á tu frente Guirnalda reluciente, Mi bien, te ceñiré;

Y eterno amor mil veces Jurándote, cumplida

En tí, mi dulce vida,

Mi dicha encontraré.

No el hondo mar te espante, Ni el viento proceloso,

Que al ver tu rostro hermoso Sus iras calmarán;

Y sílfidas y ondinas Por reina de los mares Con plácidos cantares A par te aclamarán.

My dear little fisher girl, Come to the shore,

And delight in listening

To my little love song; Seated in my little rowboat My attention is all yours,

As no lover ‘s has ever been, I’m your tender fisherman.

Night covers the sky

And the wind gently quiets down, And the motionless sea

Is calm too;

Get into my little boat,

My sweet beloved beauty,

Let the shadowy night

Be brightened by your face.

I’ll take shells and coral

And mother-of-pearl and place A shimmering garland wreath On your brow, my love;

And swear my eternal love

A thousand times and find

In you, my sweet life,

My joy complete.

Don’t be frightened of the deep sea Or tempestuous wind,

On seeing your beautiful face,

They calm their fury.

Sylphs and water nymphs Acclaim you queen of the seas With their tranquil singing;

In unison they acclaim you.

16

Pescadorcita mía…

My dear little fisher girl…

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

Rima / Poem

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer (1836 – 1870)

Te ví un punto, y, flotando ante mis ojos, La imágen de tus ojos se quedó,

Como la mancha oscura, orlada en fuego, Que flota y ciega si se mira al sol.

A donde quiera que la vista fijo,

Torno á ver sus pupilas llamear;

Mas no te encuentro á ti, que es tu mirada: Unos ojos, los tuyos, nada más.

De mi alcoba en el ángulo los miro Desasidos, fantásticos lucir:

Cuando duermo, los siento que se ciernen De par en par abiertos sobre mí.

Yo sé que hay fuegos fatuos que en la noche llevan al caminante á perecer;

Yo me siento arrastrado por tus ojos,

Pero adónde me arrastran, no lo sé.

I caught a glimpse of you, and floating before my eyes, The image of your eyes remained,

Like the dark spot and fiery rim of the sun

That hovers and blinds you.

Wherever I may fix my gaze,

I only see your glowing pupils,

But I cannot find you, just your gaze Eyes, your eyes, nothing more.

From the corner of my bedroom, I see them Gleaming at me with indierence;

When I sleep, I feel them hovering

Wide open over me

I know there are will-o’-the-wisps at night That cause wanderers to perish;

I feel myself led by your eyes,

But where they lead me, I do not know.

Text Translations: Henry Dehlinger

17

Hollins University